In December 2005, Burma’s Senior General Than Shwe ordered the start of a nation-wide campaign to plant the toxic bush-like tree, Jatropha curcas, for biodiesel production. The country was to plant eight million acres, or an area the size of Belgium, within three years. Two years on, this report documents how Burma’s people have endured forced labor, confiscation of farmlands, loss of income and threats to food security under the program. At the same time, testimonies of crop failure and mismanagement from all of Burma’s states expose the campaign as a fiasco.

Each of Burma’s states and divisions, regardless of size, are expected to plant at least 500,000 acres. In Rangoon Division, 20% of all available land will be covered in jatropha. In Karenni State, to meet the quotas, every man, woman and child will have to plant 2,400 trees.

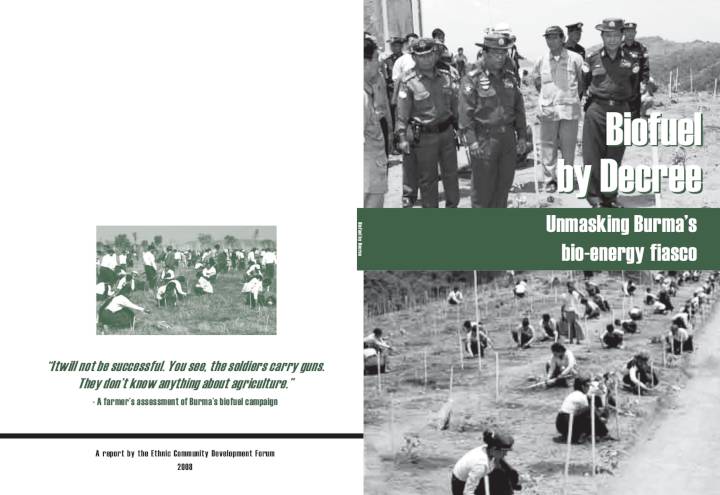

Army commanders and state officials have organized mass meetings extolling the virtues of jatropha. Photos of senior officers with watering cans and shovels have appeared in the newspapers; progress reports from around the country have been announced daily. Signboards, advertise- ments, and pamphlets have bombarded the nation.

Since 2006, all sectors of Burma’s society have been forced to divert funds, farm lands, and labor to growing jatropha. Teachers, school children, farmers, nurses and civil servants have been directed to spend working hours planting along roadsides, at schools, hospitals, offices, religious compounds, and on farmland formerly producing rice.

This radical program was started despite growing international concern about the negative im- pacts of biofuel production, especially when implemented rapidly or on a large scale.

Field research from 32 townships in each of Burma’s states, including 131 interviews with farmers, civil servants, and investors, reveals how people have been fined, arrested, and threatened with death for not meeting quotas, damage to the plants, or criticism of the program. One result of the excessive demands for farmlands and labor is a new phenomenon of jatropha refugees of whom nearly 800 have already fled from southern Shan State to neighbouring Thailand.

Plantations up to 2,500 acres in size have ignored local climate and soil conditions and been planted haphazardly, leaving up to 75% of the plants dead. Improper processing of the oil has left engines damaged and raised serious questions about the existence of adequate infrastructure to realize domestic biodiesel production. A complete ignorance of harvest yields, price, or market for the oil has left farmers and even businessmen cynical about any potential benefits of the program.

Burma’s agricultural sector is the backbone of the country’s economy and society. Policies im- pacting the sector should be considered carefully and implemented cautiously. However, with disturbing echoes of China’s Great Leap Forward to increase steel production in the 1950s, Burma’s generals are forging ahead with an ill-conceived draconian campaign, ignoring its nega- tive impacts.

This report highlights the urgent need for political reform in Burma so that agriculture is not left to the whims of generals. Sustainable agricultural policies are needed that can ensure land rights and human security and allow communities to manage their own natural resources.